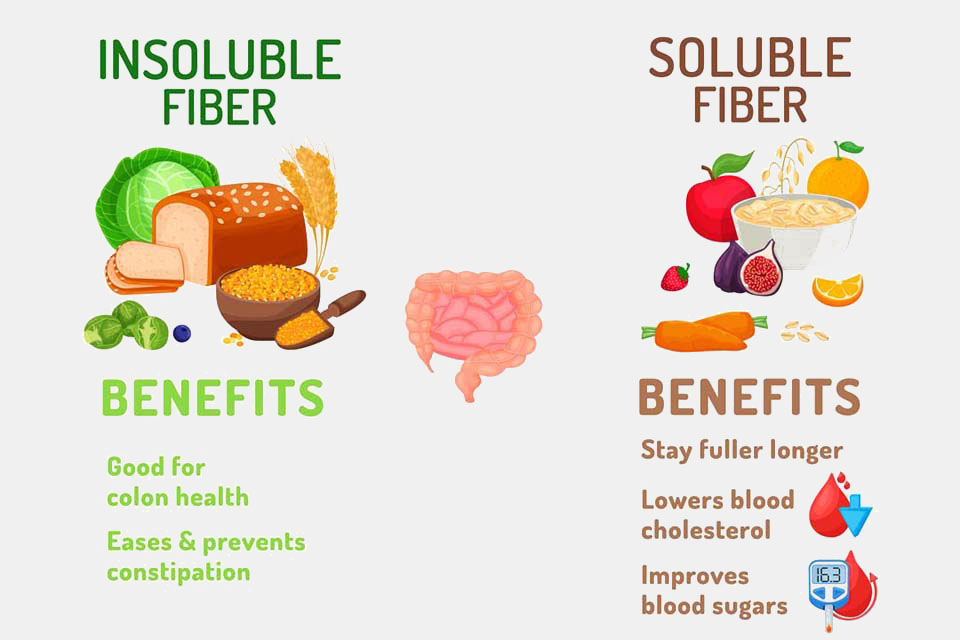

Fiber is more than just a buzzword on food labels—it’s a vital nutrient that keeps our bodies running smoothly from head to toe. Yet, when you dig into the science, you’ll discover that not all fiber is created equal. Broadly speaking, we split dietary fiber into two categories: soluble fiber and insoluble fiber. Both play unique roles in digestive health, blood sugar balance, and even weight management. Below, we’ll unfold the “who’s who” of fiber, explain why you need both types on your plate, and share simple tips for weaving more of these plant-based powerhouses into your daily meals.

Why Fiber Matters: The Basics of Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber comes from the indigestible parts of plant foods—think fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Unlike proteins, fats, and simple carbohydrates, fiber largely “checks out” during the small intestine phase of digestion and arrives in the large intestine relatively intact. There, it either forms a gel-like substance or stays bulky, interacting with gut bacteria and supporting:

- Regularity: Helping stool move smoothly through the colon

- Blood sugar control: Slowing carbohydrate absorption to prevent sharp glucose spikes

- Cholesterol management: Binding and promoting excretion of bile acids, which lowers LDL cholesterol

Soluble Fiber: The Gel-Forming Champion

How Soluble Fiber Works

When you eat foods rich in soluble fiber—like oats, apples, or lentils—those fibers mix with water in your digestive tract and form a thick, gel-like substance. Think of it as a gentle sponge: it holds onto water and slows down digestion. This slowing effect has two major downstream benefits:

- Blood Sugar Regulation

– By delaying how fast carbohydrates become glucose, soluble fiber helps curb post-meal blood sugar spikes.

– Over time, this steady release can improve overall insulin sensitivity. - Cholesterol Reduction

– Soluble fiber binds to bile acids (made from cholesterol) in the intestines, promoting their excretion.

– To replace lost bile acids, the liver pulls more cholesterol from the blood, lowering LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

Fermentation and Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Many soluble fibers—like pectins (in fruits), β-glucans (in oats and barley), and inulin (found in chicory root and onions)—become food for beneficial gut bacteria. As these microbes ferment soluble fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs:

- Feed colon cells, helping to maintain a healthy gut lining.

- Modulate inflammation, which can benefit everything from gut health to metabolic health.

Common Sources of Soluble Fiber

- Oats and Barley: High in β-glucans, which help lower LDL cholesterol.

- Legumes: Beans, lentils, and chickpeas are rich in pectin and other soluble fibers.

- Fruits: Apples, pears, citrus fruits, and berries offer plenty of pectin.

- Psyllium Husk: Often used as a supplement; clinically proven to improve bowel habits and lipid profiles.

- Flaxseeds: Contain soluble mucilage that forms a gel when mixed with water.

Read more: Could SIBO Be Behind Your Chronic Bloating? Understanding Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

Insoluble Fiber: The “Broom” That Keeps You Regular

How Insoluble Fiber Works

Insoluble fiber doesn’t dissolve in water; instead, it stays intact as it travels through your digestive tract. Picture a broom sweeping everything along: it adds bulk to stool and helps food move more quickly through your intestines. The result? Better regularity, fewer bouts of constipation, and a smoother transit time overall.

- Promotes Bowel Regularity

– By increasing stool bulk and speeding up transit, insoluble fiber prevents stool from lingering too long.

– This mechanical action can relieve constipation and help maintain consistent bowel movements. - Supports Weight Management

– High-fiber foods take up more space in your stomach without adding digestible calories.

– This leads to increased feelings of fullness, which can help curb overall calorie intake.

Partial Fermentation

While insoluble fiber is less fermentable than soluble fiber, some of it still feeds gut bacteria. The SCFAs produced are fewer in number but still contribute to gut health. The primary job of insoluble fiber, however, is mechanical—promoting bulk and movement.

Common Sources of Insoluble Fiber

- Whole Wheat Products: Whole-wheat bread, whole-wheat pasta, and wheat bran are classic sources.

- Vegetable Skins: Carrot peels, potato skins, and the rinds of cucumbers or zucchinis.

- Nuts and Seeds: Almonds, walnuts, and sunflower seeds have insoluble fiber-packed skins.

- Whole Grains: Brown rice, bulgur wheat, and quinoa.

- Corn Bran: Often found in high-fiber breakfast cereals.

How Soluble and Insoluble Fiber Differ—and Why You Need Both

Although both types of fiber travel through the digestive tract and contribute to overall gut health, they do so in different ways:

- Solubility

- Soluble fiber dissolves in water and forms a gel-like substance in the gut.

- Insoluble fiber remains intact and does not dissolve.

- Primary Effects

- Soluble fiber slows digestion, helping to regulate blood sugar and cholesterol.

- Insoluble fiber adds bulk to stool and speeds intestinal transit, promoting regular bowel movements.

- Fermentation

- Soluble fiber is highly fermentable; gut bacteria break it down into beneficial SCFAs.

- Insoluble fiber is less fermentable and mainly provides mechanical bulk, though some SCFAs are still produced.

- Key Health Benefits

- Soluble fiber supports glycemic control, cholesterol lowering, and anti-inflammatory effects in the gut.

- Insoluble fiber promotes bowel regularity, helps prevent constipation, and aids in weight management by increasing feelings of fullness.

- Food Sources

- Soluble fiber: Oats, barley, legumes, certain fruits (apples, pears), psyllium husk, flaxseeds.

- Insoluble fiber: Whole wheat products, vegetable skins, nuts and seeds, whole grains (brown rice, quinoa), corn bran.

Because they work differently, combining both in your meals offers complementary benefits. Relying solely on oats (soluble) without enough vegetables or whole grains (sources of insoluble fiber) might improve cholesterol but could leave you feeling constipated. Conversely, eating only wheat bran (insoluble) might keep you regular but won’t help as much with blood sugar spikes or cholesterol management.

Read more: The Gut-Immune Connection: How Your Microbiome Impacts Autoimmune Conditions

Practical Meal Ideas for a Fiber-Rich Diet

- Breakfast:

- Steel-cut oats topped with berries (soluble) and a tablespoon of chia or flaxseeds (insoluble).

- Lunch:

- Lentil soup (soluble) alongside a mixed-green salad featuring cucumber, carrots, and sunflower seeds (insoluble).

- Snack:

- An apple with the skin on (soluble + insoluble) plus a handful of almonds (insoluble).

- Dinner:

- Grilled salmon with a quinoa pilaf (insoluble), roasted Brussels sprouts (a mix of both fibers), and a side of sautéed spinach (insoluble).

Tips for Building Your Daily Fiber Intake

- Aim for 25–30 g of Fiber Daily

The Institute of Medicine recommends at least 25 g/day for adult women and 38 g/day for adult men. Most people only get around half of that.

If you’re new to high-fiber eating, ramp up slowly (over 2–3 weeks) to minimize bloating and gas. - Hydrate Generously

Because fiber draws water into your digestive tract, aim for at least eight eight-ounce glasses of water per day—or more if you’re active.

- Choose Whole Foods Over Processed

Swap white bread for whole-grain bread, white rice for brown rice, and fruit juice for whole fruits (with the skin on, when safe).

Add legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas) to soups, salads, and casseroles for an easy fiber boost. - Pair Fiber with Protein or Healthy Fats

Combining fiber-rich foods with protein or healthy fats (like avocado, nuts, or olive oil) further slows digestion, keeps you full longer, and stabilizes blood sugar.

- Snack Smart

Instead of chips or cookies, choose carrot sticks and hummus, apple slices with almond butter, or a small handful of mixed nuts.

Health Highlights: How Fiber Supports Your Body

- Cardiovascular Health

Every 7 g increase in total fiber is linked to a 9 % drop in cardiovascular mortality. Soluble fiber’s ability to lower LDL cholesterol and reduce inflammation drives this benefit. - Type 2 Diabetes Prevention

A 10 g/day increase in total fiber is associated with a 35 % lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Soluble fiber’s role in blunting post-meal glucose spikes is a key driver. - Gut Barrier Function & Anti-Inflammation

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by fermenting soluble fiber (especially butyrate) nurture colonocytes and tighten the gut lining, reducing “leaky gut” and systemic inflammation. - Weight Management

Diets higher in fiber lead to spontaneous reductions in calorie intake—fiber-rich foods require more chewing, fill you up faster, and help curb cravings.

Ready to boost your fiber intake and enjoy better digestive health, balanced blood sugar, and a healthier heart? Try these simple steps this week:

Subscribe to Our Newsletter. Get weekly articles, meal ideas, and expert insights on nutrition, gut health, and more delivered straight to your inbox.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not replace personalized medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional before making significant changes to your diet or lifestyle, especially if you have preexisting health conditions or concerns.

References

- Anderson, J. W., Baird, P., Davis, R. H. Jr., Ferreri, S., Knudtson, M., Koraym, A., Waters, V., & Williams, C. L. (2009). Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition Reviews, 67(4), 188–205.

- Threapleton, D. E., Greenwood, D. C., Evans, C. E., Cleghorn, C. L., Nykjaer, C., Woodhead, C., … & Burley, V. J. (2013). Dietary fiber intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 347, f6879.

- Weickert, M. O., & Pfeiffer, A. F. H. (2008). Impact of dietary fiber consumption on insulin resistance and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Nutrition, 138(3), 439–442.

- Brown, L., Rosner, B., Willett, W. W., & Sacks, F. M. (1999). Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(1), 30–42.

- Slavin, J. (2013). Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients, 5(4), 1417–1435.

- Rauma, A. L., Laye, S., & Valimaki, I. (2011). Fiber and satiety. Annals of Nutritional Disorders & Therapy, 1(3), 1009.

- Reynolds, A., Mann, J., Cummings, J., Winter, N., Mete, E., & Te Morenga, L. (2019). Carbohydrate quality and human health: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Lancet, 393(10170), 434–445.